Elsa Schiaparelli, known as the Queen of Fashion, was the supreme innovator of dress design in the first half of the 20th century. Based in Paris, she seemed to know what women wanted before anyone else, says author Meryle Secrest. But Secrest's new Elsa Schiaparelli: A Biography begins with the designer's emotionally starved, lonely childhood in a vast palazzo in Rome.

"What one has to understand about her was, that she had a very, very unpromising facade," Secrest says. "She really didn't crack a smile. She really didn't show a frown. She was impassive on the surface. But underneath were all kinds of emotional needs. She had been starved for love and affection and encouragement. And underneath all of this is someone who's daring, has tremendous intellectual ability, and who has a kind of wonderful, crazy talent."

Indeed, as a child, she tried to grow flowers on her face, to hide herself. Secrest's book follows "Schiap" (as she later called herself ) through a disastrous early marriage to William de Wendt De Kerlor, a paranormal expert who was living in London. De Kerlor, who was Swiss but claimed to be Polish, was a charismatic charlatan who posed as a count and psychic detective. It was through him and his antics that Schiap perfected showmanship and self-promotion.

Her stratospheric rise peaked as World War II engulfed Europe, and faltered thereafter, until she finally closed her atelier in 1954. But in the 1930's, she dressed all the A-list film stars, from Greta Garbo, Katharine Hepburn and Mae West, to royalty, most famously the Duchess of Windsor, Wallis Simpson. One critic said Schiaparelli "allowed clothing created out of pure, unmitigated, almost divine inspiration." She was the first to use rayon, Lurex, thick velvets, see-through raincoats, wrap dresses, trompe l'oeil bows — and she certainly followed her own advice "Dare to be different." She named a rosy hue she liked "Shocking Pink."

Secrest paints a portrait of a single mother with a sick child (her daughter, Gogo, developed polio as an infant after her husband abandoned her) and a dressmaker who, in the early days, slept in an attic show room amid mice and rats. But she was nothing if not resilient. "She didn't take no for an answer," says Secrest. "The French have a word for that. She was very debrouillard."

Schiaparelli collaborated with the surrealists of the 1930's: Jean Cocteau drew a face on the back of one gown. Alberto Giacometti was another influence. But her most famous collaboration was probably with Salvador Dali on the sexually suggestive Lobster Dress — a white dress with a giant red lobster painted down the front over the pelvis. It was immediately snapped up by the Duchess of Windsor, who posed provocatively in it on her honeymoon.

"[Schiaparelli] and Dali adored each other because they were both daring and risk-takers," Secrest says. "And Dali's theme of the lobster ... comes up over and over again in his symbolism. He has many symbols, but the lobster is really sort of sexual in theme, I suppose. And at some point or other, they both, he and Elsa concoct this idea that the lobster should be a dress."

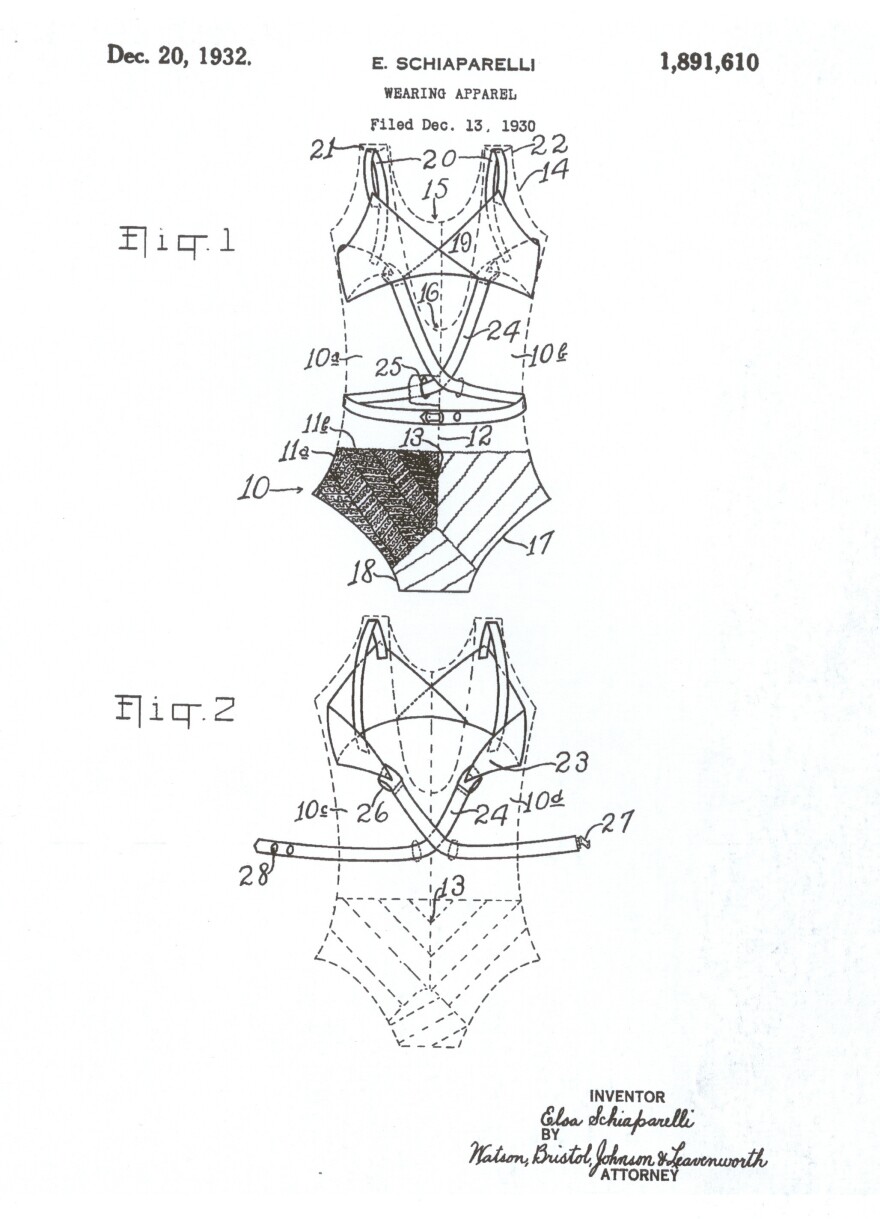

She was the first to design a built-in bra for a bathing suit, to put jackets with evening gowns, and she loved embroidery, feathers, sequins, and whimsical buttons. In her heyday, she overshadowed her great rival, Coco Chanel, and her boutique at 21 Place Vendome in Paris — with its statue of Napoleon outside the window — was the place for glamor.

Schiaparelli's movements in and out of France during the first two years of the war aroused suspicions. By the time she left France for America in 1942, the British, French, German and American governments all felt it was obvious that she was a spy for the Vichy regime. While she was in the US, the FBI watched her closely for four years and kept a file.

"The war is terrifying for every dress designer in Paris," Secrest says. "Because it goes so rapidly, because France falls so fast. People hardly have time to catch their breath. It's, it's only a year, you know. They wanted to keep their business. They wanted to keep their houses, but the Germans have moved into Paris. What are they going to do? And, of course, Elsa, being Elsa, wants to have it all. She wants to have her salon stay just the way it is. She doesn't want anybody touching her house. She wants to be able to come and go between New York and Paris. And she manages to go in and out of occupied France."

Schiaparelli returned to France after the war in 1946, never entirely free of the taint of collaboration. And herclients had moved on. Women wanted romance, not modernity. They wanted the nipped waists and flared skirts of Christian Dior's softer "New Look." By 1954, she was out of business; banks no longer lent her credit. And in 1969, she donated a collection of her clothing to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where Secrest did some of her research.

"It's a curious thing," Secrest says. "I don't think she ever was happy, you know? And I think, to a very important degree, she underestimated herself. She underestimated her influence. After all, why are we still talking about Elsa Schiaparelli? Because there are things that she did that nobody else ever did ... She's one of the greats!"

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.