Massachusetts is a blue state with a reputation for green policies. But communities of color aren't seeing the benefits.

While the high-profile deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of police have drawn national attention, there's a more insidious threat facing communities of color across the country - environmental pollution. In recent weeks, some environmentalists have drawn a connection, giving double meaning to slogans like "Black Lives Matter" and "I can't breathe."

"Literally, because of the concentration of polluting facilities, people can't breathe," says Dr. Daniel Faber, professor of sociology at Northeastern University and director of the Northeastern Environmental Justice Research Collaborative. "Black and Latino Americans breathe different air than white Americans."

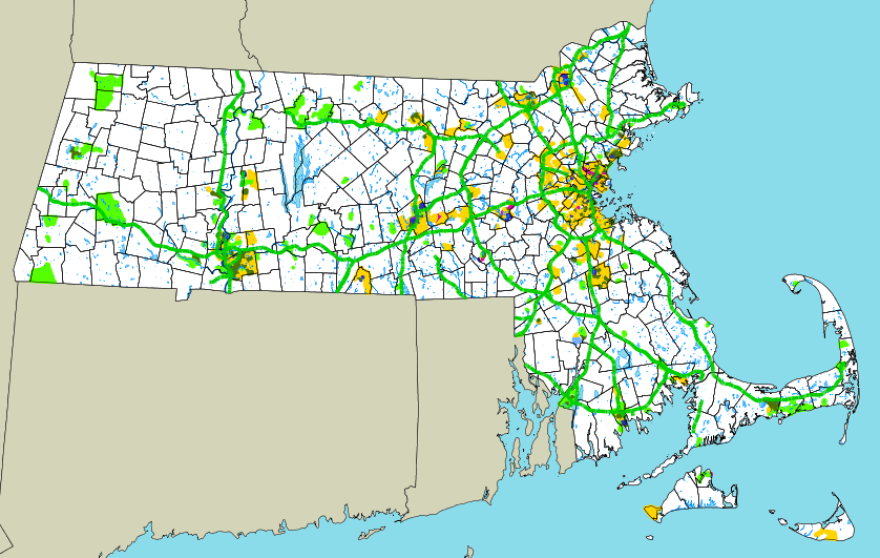

Faber says there's a widespread preconceived notion that because Massachusetts has some of the nation's most progressive environmental policies, environmental justice isn't a problem. It was precisely that assumption that prompted Faber to investigate how environmental line up with race, language, and income in the Commonwealth.

In 2001, he and colleagues released a report that shocked many, finding that communities of color in Massachusetts bear over twenty times the environmental burden of predominantly white communities. In hard numbers, that's an average of 48 hazardous waste sites per square mile and 200,000 pounds of chemical pollution released into the environment annually. In predominantly white communities, those averages are dramatically lower - just two hazardous waste sites per square mile and about 19,000 pounds of chemical pollution.

"In Massachusetts, we have some of the most profound racial and class disparities with respect to the unequal exposure to ecological hazards that you will find anywhere in the United States," says Faber.

The 2001 report prompted then-Governor Paul Cellucci to introduce the state's first environmental justice policy, but a second report released in 2005 found that the disparities were actually getting worse, not better. That was nearly a decade ago, and Faber and his colleagues haven't had a chance to analyze 2010 census data yet, but he says he hasn't seen a change in the direction things are heading. Even more worrying than the trend is what Faber sees as the cause - environmental regulations, themselves.

Here's an example. When things like landfills and ocean dumping of sewage are outlawed, here's a need for new waste disposal options, like incinerators. Nobody wants an ugly, smelly waste incinerator in their back yard, but low-income communities of color often don't have the political clout to fight back. As a result, Faber says such communities see facility after facility being sited in their neighborhoods.

Faber points to what he sees as two major gaps in current laws that enable this problem. First, since the 2001 Alexander v. Sandoval Supreme Court decision, Faber says community advocates have to prove that a company's actions not only disproportionally impact a community, but that intentional racial discrimination is at play. On top of that, there's no legal framework to account for the cumulative impacts of different polluters. So, if a power plant, a solid waste incinerator, and a hazardous waste disposal company are all looking to build in a particular neighborhood, their impacts are all considered independently.

"You have to take it case by case and prove intent to discriminate," says Faber.

Faber says the environmental justice movement is also one of the most underfunded social movements, receiving less than a tenth of a percent of all foundation grants. Much have that trickle of funds has been directed at mainstream environmental groups, rather than community-based grassroots organizations, and that has bred resentment.

But Faber says he sees changes taking place. The attempts of groups like Sierra Club, Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, and NRDC to connect with police brutality protestors is one example. More broadly, Faber says large environmental groups have begun stepping back and asking "how can we help?" instead of trying to take control. Faber points to recent alliances between ranchers and Native Americans opposed to the Keystone XL pipeline as an example.

"I think anytime you can bring together cowboys and Indians," quips Faber, "you're creating something new in American politics."